Mead judging differs from mead drinking in that the judge is thinking about the full range of perceptions and how a mead fits against idealized standards, rather than just hedonistically enjoying it. That isn’t to say that mead judges don’t enjoy their work; to the contrary, most mead judges love to judge mead. However, mead judges won’t just say that they like a mead; they will be able to explain why. They will also be able to compare one mead against another, or against idealized standards and decide relative merit. This is the skill of judging, and it must be practiced as with any other skill.

This section on judging mead discusses how to evaluate mead characteristics, how to judge mead in a competition setting, how to complete the BJCP scoresheets, and how to handle issues that arise while judging.

Evaluating Mead

Evaluation is a systematic, structured assessment of something, or a determination of merit, worth or significance against a set of standards. Good mead judges will perform an evaluation of every mead they sample, even if it isn’t for a competition. This evaluation can be performed silently and as a mental exercise, or it can be written down as notes. Regardless, this is the basic practice needed to develop the skill of assessing mead as a judge.

The structured method of evaluating mead closely follows the sequence used when filling out a scoresheet. Aroma, appearance, flavor, mouthfeel and overall impression are considered. The evaluation process focuses on capturing accurate sensory perceptions, and then comparing them against style guidelines. If used on a more recreational level, just the sensory assessment could be performed.

Assessing Mead Aromatics

In the wine-tasting world, there is a big difference between aroma and bouquet. Aroma is the smell of grapes, while bouquet is the complete smell of the wine. Aroma describes the raw ingredient and bouquet describes the character added by the winemaker. Nose is used to describe the total experience (aroma and bouquet). This is a fairly subtle distinction, since in the beer tasting world aroma generally means the total smell experience. When discussing mead, we will generally use aroma in the beer sense, although when bouquet is used it specifically includes the fermentation and age-related character. Either usage is valid.

Why are we discussing wine? Well, mead has more to do with wine than it does with beer, particularly in sensory assessment. Much of the bouquet of wine is due to the yeast used. Since mead is often made with wine yeast, the yeast-derived components will be similar. Wine evaluation techniques are also more well-developed and formalized than mead evaluation techniques, so we lean more heavily on the work of the American Wine Society in developing the framework for discussing mead.

To assess the aromatics of the mead, swirl the glass and tilt it towards you. Inhale deep in the glass, which is the lower side of the glass near the surface of the mead. Be careful, you’re judging aroma not nosefeel. Use a deep inhale lasting a few seconds, which should get heavy aromatics. Then consider what you’ve smelled. Swirl again, stop swirling, then tilt and smell again – this time towards the upper side of the glass (furthest from the mead). This will get lighter aromatics. Repeat again, smelling in the middle of the glass using a series of short, quick sniffs. Finally, keep the glass level and smell a few inches above the glass. Each of these sniffing techniques may give you a different impression.

You are looking to pick up as many different aromas as you can find. You will definitely want to assess the honey character. How strong or intense is it? Is it sweet? Does it have a noticeable and identifiable varietal honey character? Is it floral, herbal, fruity, spicy, or something else? Can you give those specific aromatics a name? Honey is to mead as grapes are to wine; you need to describe the character of the primary ingredient, and relate it to any expectations you may have given how the mead was described.

Now assess the fermentation character. Did the yeast add any interesting aromatics (fruit, spice, etc.)? Is there alcohol noted? Are there any fermentation faults? If a certain type of yeast was mentioned (Flor sherry, for example), does it have the characteristic aroma? Alcohol can definitely be sensed. If it is sharp and aggressive to the point where it overwhelms other components, it is a negative. Alcohol level should match the style of mead. Refer to Troubleshooting Faults for a list of common mead characteristics; many of them are detectable by aroma. Do they persist or do they blow off quickly? Characterize the overall fermentation character: is it clean, fresh, dirty, yeasty, sulfury, or something else?

Were there any special ingredients (fruit, spice, malt, etc.) used in this mead? If so, do you detect their presence? If a special ingredient is fermentable (e.g., fruit), then the character might not have the same impression as the fresh ingredient. For example, wine does not smell like grapes, it smells like fermented grapes – don’t expect fruit in a mead to always smell like the raw fruit, the fermented character can be different. The amount of residual sugar in the mead can affect the impression of fruit, since fruity aromatics are often found with sweetness in fresh fruit. Declared special ingredients should be noticeable, but balanced and in harmony with other ingredients.

Acidity can often be sensed in the aroma, but tannin cannot (unless tied to oaking). Acidity that comes from fruit or yeast can often be sensed more readily in the aroma than those made by acid blend additions. Carbonation often will play up the nose since the bubbles help volatilize aromatics.

Was there any special processing (e.g., oak aging) used in this mead? If so, do you note the character? Oaking will often impart a woody, toasty, vanilla character. Other special handling techniques will produce aromas as well. Icing will concentrate aromatics. Intentional oxidation (e.g., for Polish meads) will obviously introduce an oxidation character.

Finally, you want to consider the overall balance, harmony and pleasantness of the mead. Do the ingredients complement each other? Are they in balance given the style and declared attributes (strength, carbonation, sweetness, special ingredients) of the mead? What is your overall impression of the quality of the mead? Is it well-made and use good ingredients? Does it have an off odors? Is this something that you are eager to now taste?

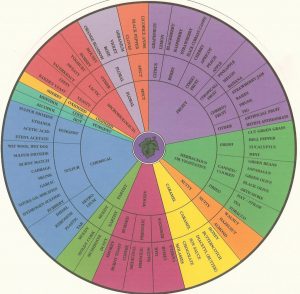

The Wine Aroma Wheel is a tool commonly used in the wine judging community. While wine does not have exactly the same aromatics as mead, there is a substantial overlap. Until such time as an equivalent mead tool is developed, it is probably the most useful descriptor aid we have. As you progress from the center to the outside of the wheel, the descriptors become more specific. Use this to help you better describe your impressions. You are likely to initially pick up the characteristics closest to the center. See if you can further characterize them by moving outward on the wheel. Not all possible aromatics are listed; just those that are commonly found in wine. Do not feel constrained to use only these terms. If you note something that can be accurately described using equivalently-descriptive words, by all means go ahead.

Widely used by the wine judging community, buy one at www.winearomawheel.com

Assessing Mead Appearance

Assessing the appearance of mead is easy, right? Just note color, clarity and carbonation and then move on. Not so fast. Again, assessing the appearance of mead is more akin to evaluating wine than beer. We will use the techniques of wine judging to give us insight into mead, by assessing color (hue, saturation and purity), reflectance, clarity, legs, carbonation (mousse, cordon, size of bubbles, persistence of bubbles).

To describe the color of a mead, start with the hue (also known as shade). This can range from nearly water-white all the way to dark brown, although added fruits, spices, malts, and other ingredients can introduce a new color spectrum. The vast majority of honeys ferment to a water-white to dark amber range, with straw to gold being the most common. Common color descriptors include water-white, straw, yellow, gold, and amber, with some ranging into copper and brown. Each color descriptor can be further described within its range by using the adjectives light or pale, medium, and dark or deep.

Melomels can take on more vibrant yellow/orange, red and purple colors, using descriptors such as pink, salmon, orange, red, ruby, crimson, purple, and brick. Almost any color variation is possible, so draw upon your vocabulary to think of the appropriate color (channel your inner child to recall your Crayola 64 box) – give the color a name. Accurately describing the color provides a linkage to the ingredients used; if the color is not suggestive of the declared ingredients, there could be a problem. View against a white sheet of paper to get an accurate color reading.

Saturation or intensity is the depth of the color of a mead, and describes the lightness or darkness of the hue. For example, scarlet is a saturated color, while pink is not. Describing the intensity of a color might give clues into how much of an ingredient was used, or be indicative of certain ingredients. Some colors are described as deep or inky, which indicates greater intensity. If the mead is dark or intense in color, tilt the glass and view the shallow edge of the liquid. View against a white sheet of paper or in front of a light source to view the saturation level.

The purity of a mead is described as the correct or appropriate color for its age, showing no water edge (meniscus), and no oxidation. Brownish, dull or muted colors might be suggestive of oxidation. The color at the meniscus (rim of the mead when tilted in a glass) is indicative of concentration, maturity and richness. The more variation in color, the older the mead. An evenly colored meniscus usually indicates a younger mead. More intense colors can indicate a greater saturation, while dulled colors can indicate oxidation.

Reflectance describes the mirror-like surface of the mead, which is a positive attribute. If the mead surface is dull or has a flat appearance, it can suggest a lack of fining or filtering, or of possible spoilage.

Clarity describes the ability to transmit, absorb, or reflect light. It is often a measure of a mead’s health, or of the care taken by the meadmaker. Descriptors range from brilliant (perfect crystal clarity), bright (slightly less than brilliant), clear (acceptable clarity), dull (minor clarity problem), hazy (serious clarity problem), to cloudy (unacceptable clarity). Check the mead for uniform clarity or the presence of crystals, flakes, particulates, or other “floaties” that can detract from the visual presentation. Stronger meads can have a gem-like depth to their clarity. Higher degrees of clarity are more desirable, as is the absence of any floating particulates.

Note that chilled meads can produce condensation on a glass and may seem like cloudiness. If the glass feels wet, wipe away any condensation before attempting to judge clarity (or other appearance attributes).

Assessing legs gives an indication as to the body, alcohol level and sweetness of a mead; it has nothing to do with quality. Swirl the glass gently and then let the swirled liquid glide slowly down the side of the glass. Look for rivulets or tearing that may appear; these are the legs. Meads with legs have higher alcohol, sugar, or body. The rate that the legs glide down the glass gives further information (the slower the tearing, the higher the alcohol, sugar or body). Wine judges often call legs by the names tears (the kind from crying, not ripping) or arches.

The final observation is about the carbonation. Not all meads are carbonated, so there might be nothing to describe. Note the height of any head that forms (quantity), how fast the bubbles form (rate), and how long the head persists (duration). Note the size of the bubbles. Did the bubbles form a mousse (head) or a cordon (bubbles around the rim)? Are there bubbles on the bottom of the glass, and do they rise? Characterize the carbonation (still, petillant, sparkling), realizing that still meads can have a few bubbles and sparkling meads do not have to be fizzy like soda pop.

Assessing Mead Flavor

When assessing the flavor of a mead, look for similar characteristics as in the aroma: honey character, sweetness, alcohol, acidity, other ingredients, and special processes. Also look for additional flavors such as bitterness, sourness and the mouthfeel of tannin, particularly as it relates to the flavor balance. Flavor, mouthfeel and aftertaste and typically considered together in mead rather than separately, as they may in a beer evaluation.

Even though you may look for individual components and try to accurately describe them, keep in mind the overall balance. The primary concern is the balance and harmony of the mead, both the acidity-sweetness-tannin balance and the balance between the honey tastes and the other tastes (such as fruit or spice) that are present in the mead. The individual components are important, but not as much as the overall impression and how well the mead relates to the expectation established by the mead style and the declared attributes (sweetness, carbonation, strength, special ingredients).

Before we talk about tasting, we first have to clear up a huge misconception about taste: the tongue map. (You know the one; it shows the tongue as tasting sweetness at the tip, bitterness at the back, and sour/salty at the sides.) While the tongue taste map has been debunked, it still frequently appears in literature. Flavor receptors exist all throughout the tongue and all tastes can be sensed in all areas. There are localized regions of higher sensitivity to certain tastes, but that does not imply that other areas do not sense those tastes. The maps also leave out the fifth basic taste, umami or savoriness. The bottom line is that to properly taste something, you should involve your whole mouth, tongue, and palate.

To assess the flavor of a mead, there are several techniques that can be used. All involve taking small sips; mead can be quite strong, so taking gulps is a quick way to shorten your effectiveness as a judge. Take a sip into the front of your mouth and swish the tip of your tongue through it. Take a sip and move your tongue side-to-side to swish it through your mouth. Take a sip and let it rest on the top of your tongue. Take a sip and aerate the mead by breathing over it in your mouth (it will make a slight slurping or gurgling sound). Take a sip and swallow, focusing on the aftertaste. After swallowing, keep your mouth closed and exhale through your nose. You may pick up additional aromatics this way. These techniques can be combined. They each involve different areas of your mouth and may give you additional flavor impressions. As you develop your tasting skills, you may decide to use different tasting techniques to look for different flavor or mouthfeel elements.

The first task is to characterize the honey flavors and sweetness. Do you get a distinct, clean honey flavor or is it muddy and indistinct? Is there a varietal honey character you taste? Is it distinct and unmistakable, or rather generic? How well does the honey flavor blend in with the other flavors? How strong or intense is the honey flavor? How would you describe the honey character? Is it floral, fruity, spicy, herbal, or some other flavor?

What is the level of sweetness? Common descriptors include: bone dry, dry, off-dry, slightly sweet, moderately sweet, moderately-high sweet, sweet (or high sweetness), very sweet, or cloyingly sweet. Do not confuse sweetness with fruitiness or honey flavor – sweetness is only a measure of residual sugar.

Next look for the structural elements of acidity and tannin, which balance the honey flavor and sweetness. Acidity is the tingle, tartness, zing or liveliness in a mead. It can be described as flat or flabby (not enough acid), pleasant (balanced), tart (acidity is forward) or sour/acidic (high acidity). Low acidity is soft, plump, smooth, while high acidity, is crisp, tangy, tingly, and mouthwatering. The level of acidity usually isn’t described in absolute terms, but rather in the balance when compared to sweetness. Tannin can be described in low to high terms (see Mouthfeel for specific descriptors). The overall balance of acidity and tannin to sweetness and honey flavor should be noted.

Alcohol flavors and bitterness can be described next. Alcohol does have a taste but it is usually sensed as a warming (good) or burning (bad) mouthfeel, if noted at all. Higher alcohol levels can introduce bitterness. Bitterness is not very common in mead, although there are ingredients that might introduce some. Alcohol and bitterness can affect the overall balance, and should be noted if detected. As with strong beer and wines, the best meads often have a “sneaky” quality to them where the alcohol is often felt more than it is tasted.

The special ingredients and processes can add another whole realm of flavors: fruit, spice, malt, oak, etc. Some honeys and yeast can produce flavors that mimic those from fruit and spices. However, if there are special ingredients declared, those should be noticeable and generally identifiable but well balanced and harmonious with the other ingredients (relative to the style and intent of the mead). Entire books have been written on characterizing flavors such as these. Try to generally describe the character and strength of each flavor component you detect. See if you can give it a name (e.g. cinnamon) or at least a general description (e.g., spicy), and an intensity (light, moderate, strong). The more descriptive you can be, the more information you are passing along.

Normally, yeast-derived flavors are mentioned along with discussions of fruit, spice or alcohol. However, if there are fermentation flaws, those should be noted. See the list of characteristics in Troubleshooting Common Faults for more information – most of the faults can be tasted. If no fermentation issues are noted, identify the mead as having a clean fermentation.

The aftertaste of the mead is the flavor impression you get once you have swallows the mead. You can describe the length (short, medium, long, memorable) of the aftertaste, which is the duration it takes for the flavors to dissipate. What kinds of flavors are you getting in the aftertaste? Are they different from flavors noted when tasting the mead? Are they pleasant and balanced? Is there anything off?

Note that taste perceptions can be influenced by mouthfeel textures. Alcohol enhances the perception of sweetness, reinforces acidity, can mask odors, and may cause a burning sensation. Astringency may have a rough, gritty character and can mask bitterness and reduce the perception of sweetness. Bitterness is often confused with astringency (bitterness is a taste, astringency is a mouthfeel).

The overall balance of the mead should be described. Balance is relative to the specific style of mead and its attributes (sweetness, strength, carbonation, special ingredients). Balance does not mean that flavors are in equal proportions or intensities – a sweet mead will definitely have more sweetness than a dry mead, yet both can be balanced. A sweet mead requires sufficient acidity and/or tannin, or it will seem flabby. Balance describes how well the individual components complement each other in the intended style of the meadmaker.

When discussing balance, identify if any components are too strong or weak. Does any individual component overshadow the mead, even when taking style into account? Is there any component that is lacking (e.g., not enough alcohol in a sack mead)? Are the special ingredients identifiable yet not overly dominant? The best meads are not one-dimensional; they have interest and character. They do not all have to be complex; dry, delicate, restrained meads can be wonderful. Do not attempt to equate a dry hydromel to a sweet sack mead in complexity and character; judging them each on balance relative to their intended style is the best way to level the playing field.

Keep the aroma in mind when evaluating the final taste of the mead. Do the flavors you get match what you expected given the aroma? Do the flavors mirror the aromatics? For example, if you smelled blackberries, did you taste them as well? Are there any additional flavors? If so, what are they? Is the mead balanced? Are the tastes present in the proper proportion given the style and declared attributes? These questions often will give you the best idea of the overall impression of the mead.

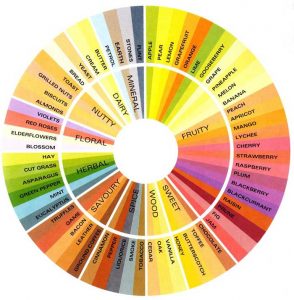

An example of a flavor wheel for describing wine was found online (the original source was in Australia), but it is not widely used in the wine judging community. However, the basic idea is sound and can be applied to mead. This is less of a guideline than merely an example of how flavor descriptors can be organized. Use it when developing your own lexicon and when learning the various flavor elements in mead. Start with a broad characterization of the flavors you sense, and then see if you can give them specific names. The names don’t have to be fancy; whatever mental association you have with the flavor is sufficient if it conveys information.

(Not widely adopted)

Assessing Mead Mouthfeel

Mouthfeel describes the non-flavor sensations in your mouth when you taste something. It includes the tactile sensations, the textures, and the feelings associated with drinking. The sparkle of carbonation, the warmth of alcohol, the sharpness of acidity, and the roughness of tannin are all mouthfeel characteristics. The body of the liquid provides weight on your tongue, and may coat your mouth. Tingling, numbing, drying, cooling, warming and coating are all mouthfeel sensations. Mead can be described in textures such as smooth, soft, velvety, rough, hard, or harsh. Since the tannin level of mead is important to the overall balance, it is not as easy to separate flavor from mouthfeel as it is in beer. Flavor, mouthfeel, and aftertaste are best judged together.

The most straightforward components of mouthfeel in mead are the same ones used in beer judging: body, carbonation and alcohol warmth. Body is a measure of the relative viscosity of mead (weight of the mead on your tongue), and can range from light/thin to medium to heavy/full. These are the normal ranges for body, but a mead could have lighter or heavier body as a fault. A very light body is described as watery, while a very full body is viscous, thick or syrupy. As a very general analogy, light body is like skim milk, medium body is like whole milk, and full body is like cream. The perception of body is influenced by alcohol and sweetness levels; stronger and sweeter meads will seem to have a fuller body.

Carbonation describes the level of dissolved carbon dioxide in solution, and ranges from still (lightly carbonated) to petillant (moderately carbonated) to sparkling (highly carbonated). Still does not imply totally flat, a light level of carbonation is acceptable. Sparkling has a fairly wide range as well, with spumante being used for the highest level of carbonation. High levels of carbonation could also be described as effervescent, while fizzy and gassy are typically negative terms implying too much carbonation. Bubbly and Champagne-like are more positive terms, when applied to sparkling meads.

The alcohol in a mead can be unnoticeable, or provide a pleasantly warming sensation to a hot burn. A smooth warming quality is a positive character in a stronger mead. Hot, solventy, burning sensations are always a negative. Stronger meads should have noticeable alcohol, but the alcohol should be well-blended and balanced with other flavors. Higher alcohol generally is perceived as having increased body, more warmth, and perhaps a bit more bitterness.

The acidity in a mead might be noted, particularly if it becomes sharp, puckering or tingly. A well-balanced acidity is more commonly noted in the flavor section. High levels of acidity might affect mouthfeel in a generally negative way.

Tannins in mead definitely affect mouthfeel. Astringency, dryness and puckering are common characteristics, particularly when tannins are over-used; note any of them. A pleasant balance might not be noted in mouthfeel, but excessive tannins should always be mentioned. Oaking the mead can introduce tannins in addition to flavor elements.

When describing mouthfeel, try to separate the flavor components from the mouthfeel components. The astringent, mouth-puckering qualities are what should be described in the mouthfeel section. The range of terms used to describe astringency includes: not astringent, smooth, soft, velvety, slightly rough, moderately astringent, rough, harsh, very rough, coarse, tannic, and highly astringent. Astringency tends to moderate over time as the mead ages.

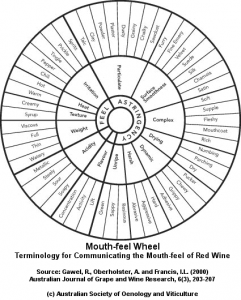

An example of a mouthfeel wheel for describing red wine was found online (the original source was in Australia), but it is not widely used. However, the basic idea is sound and can be applied to mead. This is less of a guideline than merely an example of how mouthfeel descriptors can be organized. Use it when developing your own lexicon and when learning the various mouthfeel elements in mead.

Basic Mechanics of Mead Judging

Mead judging is slightly different from mead evaluation in that it is a structured evaluation of mead in the context of a competition. The basics of evaluation are still present, but the perceptions are recorded in a structured manner on a scoresheet along with feedback to the meadmaker. Numerical scores are assigned, as are relative rankings that determine awards. Entrants pay for this feedback and scoring, so it is your duty to give the judging your best effort.

As a mead judge, you have been called upon to give your impression and objective critical opinion of the meads in the flight placed before you. Just how is this accomplished? If you have judged beer in the past, you already have most of the basic skills and knowledge necessary to judge mead because the procedures to judge beer and mead have much in common. However, mead judging does have its own idiosyncrasies and deserves its own discussion.

Getting Ready for the Flight

Before the meads are brought to the judging table, look over the information provided by the competition organizer. This should include a set of style guidelines explaining the standards against which the meads are to be judged. Make yourself familiar with the specific styles in your flight, and discuss the characteristics you will be looking for with the other judges at the table.

There should also be a list of the meads to be judged in your flight, along with the specific modifiers (variety of honey, strength, sweetness and carbonation level) for each mead. Go over this list and decide on the order in which you would like to judge the meads. In general, start with meads that are drier and lower in alcohol than ones that are sweeter and stronger. Think about the overall palate impact of all the ingredients in the mead (including fruits, spices and other ingredients), and judge them in increasing order of intensity. This helps preserve your palate so it won’t get overwhelmed by strong tastes early in the flight, and so that you will be able to fairly judge each mead.

Discuss the judging order with your steward, as well as the serving temperature. Depending on how the meads have been stored, you may wish to pull some or all of the meads so they can warm up. Ask if any of the meads have corked bottles; if so, make sure a corkscrew is available.

Finally, take note of the number of meads to be judged in the flight. If there are a large number, remember to take smaller sips so you can avoid becoming intoxicated. Pace yourself and remember to drink water between meads to clear your palate and to stay hydrated. If you start feeling the effects of the alcohol, slow down and have some bread and water. Take a break and stretch your legs if necessary.

Judging a Single Entry

Most judges develop a personal method for judging mead through experience. Here we outline a general process that is known to work and that may be used as the basis of your personal judging regimen. The process is somewhat independent of the scoresheet used, since that aspect of judging concerns capturing your perceptions, opinions and judgments rather than conceptualizing them. This process ensures that you will give a complete evaluation to each mead you judge.

- Fill in the scoresheet header, including information about the mead and yourself. Use pre-printed labels if provided, or your personal judging labels if you brought them.

- If possible, do a bottle inspection before serving each mead, looking for fill level, bacterial rings (a rarity in mead), and sediment level. Green or clear bottles are fine, as skunkiness shouldn’t be a problem in meads (unless it is a hopped braggot). Don’t prejudge the mead; simply note the information in case you need it to help diagnose a problem.

- Open the mead and pour one to three ounces. Decant slowly off any sediment that may be present. Note that sediment in mead may not be as tightly packed as in beer, so be careful in agitating the bottle. Pour all glasses before righting the bottle; tilting the bottle back and forth will certainly rouse sediment if present.

- After pouring a sample, quickly inhale the aromas. Use long, deep sniffs or short, shallow sniffs – whatever works best for you, as long as you are consistent for all meads judged.

- Write down your initial impression of the aroma and bouquet. Comment on the honey character, the fermentation character, the presence of other ingredients, and the overall balance, harmony and pleasantness of the mead. Use the methods described in Assessing Mead Aromatics. Try to be specific when describing your perceptions, and be sure to quantify them (i.e., how strong are they?). Talk about the relative balance of the perceptions. Comment on any expected perceptions for the style that are present or absent. Use descriptive language rather than personally subjective terms (e.g., “strong, floral, orange blossom-like aroma” rather than “good aroma”).

- Move on to Appearance. Comment on the mead’s color – try to name it specifically: water-white, pale straw, deep golden, medium amber, etc., and relate it to the style expectations. Note the clarity: cloudy, turbid, clear, brilliant, opaque. Again, what does the style require? Finally, note any carbonation. A still mead with slight carbonation should not merit a big deduction, but in general the carbonation level should match what was declared by the meadmaker. Be sure to make notes of everything you detect about the appearance.

- Now smell the mead again and take a slow sip. Form an initial impression from the first taste, and allow it to linger a few seconds before swallowing. Note the finish (as you swallow) and aftertaste (a few seconds later). Consider the factors described in Assessing Mead Flavor. As with aroma, try to be specific about describing what you are tasting and identifying the relative strength. Where in your mouth are you tasting it? How does it feel on your tongue? Note the presence or absence of any required style characteristics. Describe any faults if present. Be sure to note the balance from start to finish and into aftertaste.

- Assess the mouthfeel of the mead. Consider the factors described in Assessing Mead Mouthfeel. Be complete and describe body, carbonation, alcohol, astringency and other sensations. Note whether the attribute is appropriate for the style.

- In the Overall Impression section, give your general impression of the mead. Give objective comments on how the mead fits the intended styles. If flaws are noted, point to possible causes.

- Make sure to cleanse your palate between entries with water, bland bread or a cracker. Do your preliminary judging and scoring in silence so that you do not influence the other judges. The entrant will benefit more from several independent judgings than from several version of the same outspoken judge’s opinions. Regardless of how you assign scores, put the most emphasis on giving complete and thorough written comments, because they will matter more to most mead makers than the overall score.

There are several important points to keep in mind throughout the judging process. First off, avoid negative comments. Emphasize the mead’s positive attributes, even if it is awful. Diplomacy is a valuable skill as a mead judge. Also, try not to be too specific, since you do not know how the mead was made.

Make sure any checkboxes describing the mead are appropriately checked, whether it involves identifying off-flavors, or simply describing your view of the stylistic, technical and intangible merits of the mead.

Note that an experienced mead judge should be able to completely perform a written evaluation in about ten minutes. The scoresheet should be completely filled in, legible, and added correctly. The assigned score should agree with the comments, and should make sense when compared against the Scoring Guide.

Finally, the most important thing is that a good mead evaluation should provide a thorough sensory evaluation. Make sure the entrant understands what attributes the mead has (or doesn’t have) that justify the score. Opinions are best kept to yourself, but if you can offer any constructive advice, it is worthwhile to do so. Just keep in mind that you don’t know what the meadmaker did, so you are at best making educated guesses when you offer advice.

Preparing Scoresheets at Competitions

While the prior section is adequate to describe how to judge mead by yourself, competitions aren’t run like that. You will always be assigned to a judging team, and you will have to interact with other judges. The manner in which you assign a score and then work with your team will in large part determine your success. While you will not judge meads as a team on the exam, your scoring will be assessed against the proctor panel of high-ranking judges. Your scores will also be compared against other examinees. If you haven’t had the opportunity to judge with other BJCP judges and develop a sense of scoring calibration, the following discussion will be of value to you.

The Standard BJCP Scoresheet

Although evaluating mead is an inherently subjective task, preparing high-quality scoresheets is not. This section is not about how to gain better perception skills, how to describe what has been perceived, or how to provide feedback to the meadmaker. Rather, this discussion is focused on how to score a mead, and how to calibrate scoring with other judges, and how to reach a consensus during judging. These skills often distinguish an effective mead judge from simply being a knowledgeable taster. A good judge should be able to tactfully apply judging techniques in practical situations to produce accurate and helpful scoresheets.

Scoring Methods

There are generally three approaches to scoring meads. The first technique assumes that a mead starts with a perfect score of 50. Points are then deducted for style and technical issues to get to the target score. The second method starts by assigning the mead zero points, and then adds points for each positive characteristic to reach the target score. The third approach starts in the middle, and then adjusts upward or downward based on comparison to an average mead.

A problem with the first two approaches is that there is no defined specific point allocation for each potential characteristic, whether present or not or in the correct percentage. There is some general guidance but it is not at a granular enough level to be applicable. For example, under Flavor there are 14 points allocated to “balance of acidity, sweetness, alcohol strength, body, carbonation and other ingredients as appropriate” – OK, how do you assign points for that?

Judges who successfully use one of these two methods generally create an allocation points for each of the cues (as is done well in the Appearance section, where color, clarity, and carbonation are each allocated two points). The judges then add or deduct points based on how well each cue is represented in the mead. This approach requires significant judgment and experience to do properly, but is often the most analytical solution.

The Aroma section is worth 10 points but only has two cues: expression of honey, and expression of other ingredients. What about traditional meads? There are no “other ingredients” – does that mean that you can only give a traditional mead five out of ten points? Of course not. Judges think about what components belong in a perfect example of the given mead (e.g., honey varietal character, esters, fermentation character, alcohol, sweetness, complexity, etc.) and assign points accordingly.

For each defined characteristic, the judge would assess how well it meets the style guidelines or whether it contains faults. A full score is given to a component that is properly represented, while a low score is given to a characteristic where there is a problem. The component scores are summed to get the overall section score.

The third approach starts at a neutral point of scoring in each section, especially Aroma, Flavor and Overall Impression sections, and then adds or subtracts points depending on whether the characteristic is better or worse than an “average” example of the mead. For example, if the aroma of a specific mead in a stated style has stylistic or technical faults, then subtract from the mid-point of six. If there are positive qualities to the aroma that exemplify the style, then add points until you approach the ideal score of 10.

This approach works well for the Flavor section as well. A mead that has neither faults nor particularly good qualities could earn the mid-point score of 12. As the flavor more exemplifies the qualities of the style, award points to approach the ideal score of 24. If technical or stylistic faults are present that detract from the flavor expectations, then subtract points from the mid-point score of 12.

For the Overall Impression section, the same approach is also successful but can be modified by considering how the mead ranks in one’s experience and desire to drink more of the mead. A mead that is nearly perfect and commercial quality would receive a score closer to the ideal 10, while a mead that is just undrinkable might receive a score closer to the bottom of the scale. In the middle is the mead that isn’t particularly good, but not terrible either.

The choice of approach often depends on the personality and experience of the individual judge. Very experienced judges can often quickly assign a “top-down” or holistic score based on overall characteristics. Very analytical judges (of any experience level) will often the “bottoms-up” method of assigning and totaling individual component points. Each can be effectively used in practical situations, provided the final assigned score accurately represents the quality and style conformance of the mead.

Regardless of scoring method used, there is a need to perform an overall scoring sanity check after the initial score has been determined. Experience will enable a judge to quickly assess an appropriate score for a mead within the first few sniffs and sips. Until that skill is learned, the Scoring Guide printed on the scoresheet provides a reference for the score range of meads of varying quality. After adding up the total score from the individual sections, check this against the Scoring Guide listed on the judging form. If there’s a discrepancy, review and revise the scores or the descriptions so that the score and the description in the Scoring Guide are aligned.

Scoring Calibration

Since we don’t want to completely discourage a meadmaker, most judges will skew scores away from the very bottom of 50 point scale with an unofficial minimum of 13. It is acceptable to go below 13 for extremely infected examples or meads that are essentially undrinkable, but this should be done only in rare circumstances. Many judges, particularly ones who learned using older versions of the scoresheet, use a practical minimum of 19 for all but the most horrific examples.

Likewise, many judges don’t award scores high into the 40s because they either tend to find faults when there are none, desire to reserve space for a higher score should a better mead in the flight be presented, or are fearful of having to defend the bold position of awarding a high score to their judging partners.

These self-imposed constraints mean that the full 50 point scale often isn’t used. Don’t worry excessively about that; there are few absolutes in scoring. In competitions, the scoring and ranking are not only subjective, but more importantly, relative. Give the mead an honest and thorough organoleptic assessment and make sure the best meads get the highest scores. Strive to keep the scores of individual meads aligned with their relative rank within the flight. If you maintain scoring calibration throughout the flight, you won’t need to go back and retaste meads once the flight has concluded.

Many judges develop certain heuristics for assigning scores to meads with certain problems or characteristics. The Scoring Guide on the scoresheet gives a general feel to these categories, but the specifics are rather sparse due to space limitations. Some judges use a system such as:

- A clearly out-of-style mead is capped in score at 30

- A clearly out-of-style mead that does not have technical faults bottoms out at a score of 20

- A mead with a single bad fault is capped in score at 25

- A mead with a bad infection is capped in score at 20

These simple rules help a judge move a mead into the right scoring range quickly. Within these ranges, meads with more faults or with worse faults score at the lower end of the range. In general, meads with technical faults score lower than mead with style faults since technical faults usually affect overall drinkability and enjoyment to a greater extent. Meads with fermentation faults are often punished the most, since fermentation is at the heart of creating mead.

Scoring Reconciliation

This brings us to the reconciliation of scores between judging partners. Some organizers will ask judges to score within seven points of each other, while others will target a less than five point spread. Three points or less is really the ideal target; it provides the best feedback to the meadmaker in terms of confidence in the evaluation.

Simply calculating the arithmetic mean of the scores will result in an average score that conveys information as the consensus for the mead. However, the variance (distance of individual scores from the arithmetic mean) implies additional information. Higher variances indicate greater dispersion in scores, and imply a larger disagreement about how the mead should be valued. When judges have a low variance in score, the meadmaker will see a more consistent message and believe the final assigned score is more credible.

Regardless of the desired point spread, there are frequently occasions where judging partners must decide on a consensus score for a mead about which they fundamentally disagree. There are many different techniques for reaching a consensus score, and several best practices for resolving disputes.

First of all, remember that judging is subjective. Differences of opinion can exist for a variety of reasons between skilled judges with good intentions. If judging was truly objective, then a score could be determined solely by lab analysis. Remember, there is not necessarily a “right” score for a given mead.

Judges should strive for a common understanding of both the mead being judged and the style guideline against which it is evaluated. If judging partners are in agreement as to the style and to the mead, then they should be able to agree on scoring within a small range. Use the Scoring Guidelines printed on the scoresheet as a reference.

Differences of score usually are derived from a disagreement on the style or more typically on the perceptions and faults in a mead. Seek to narrow down the basis of disagreement and see if those points can be resolved. If opinions change as a result of discussion, then scores and comments on the scoresheet should be adjusted accordingly.

If judges are far apart in score, try to understand the basis for the difference. The judges should ask each other what they perceived that caused them to score the mead the way they did. Compare the basis each judge used for assigning their initial scores. See if you can isolate the reasons for the difference in scoring.

If the differences are based on conformance to style, refer to the Style Guidelines and see if you can agree on the style definition using the Guidelines as the referee. They are really quite detailed and specifically designed to help in this purpose. If all judges have tried commercial examples, discuss your memory of them. Compare the mead being judged to classic examples of the style. If one of the judges has an incomplete understanding of the style, try to resolve that knowledge gap and then rescore the mead. Tact is critical, as a judge whose knowledge level isn’t up to the top level may become defensive.

If the differences are based on a perception of an attribute of the mead, or perception of a fault, try to come to a common agreement on whether that attribute/fault is present in the mead being judged or not. Maybe one of the judges has a higher threshold for perceiving the attribute (for example, a sizable portion of the population cannot sense diacetyl.) Maybe one of the judges isn’t familiar with how to perceive a certain fault. If one of the judges realizes their perception is wrong, then recalculate the score based on that new understanding.

If the judges agree on the presence of a technical or stylistic fault, ask how each judge weighted the fault. Some judges may deduct more for faults than others. Simply entry errors in sweetness or carbonation, such as describing a mead as sweet when it is really medium, should not merit much of a deduction. These levels are often fairly subjective. Reserve major deductions for real issues in the mead, not trivial issues.

If you discuss the mead with your judging partner and find that your perceptions differ, you might note on your scoresheet that the other judge got <fault> and you didn’t. The entrant might be able to infer that different judges have different perceptions and they can take that for what it’s worth. Believe me, entrants are used to judges saying contradictory things. If you address it head on, at least they will understand what happened.

If the judges can’t agree whether a fault is present or not, they may ask for another opinion. This is not something that should be done very often, but they could ask a highly regarded judge from another panel (or an organizer or staff member) to confirm if something is there or not. Be sure to ask that judge if they have an entry in the flight before their opinion is sought, however. This is just about the last resort for resolving a difference.

If judges still can’t agree on a consensus, then it’s best to agree to disagree. Keep each scoresheet as originally written and just average the scores for the consensus. See if the judges then agree with the assigned score. That will usually work. The meadmaker will see that a strong disagreement existed and perhaps conclude that their mead was either a “love it or hate it” experience.

If you consider that advice extreme, consider the following actual case: A high-ranked BJCP judge once was partnered with a professional brewer in a homebrew competition. The pro brewer listed few comments on the scoresheet, wrote in pen, and wouldn’t accept anyone else’s opinion. The judge tried several times to engage the brewer in discussing meads, but the brewer wouldn’t budge and didn’t really care about other opinions. The judge simple wrote off the flight, and decided further discussion was pointless. Each judge wrote their scoresheets and assigned their scores. The scores were averaged regardless of the difference, and the next mead was brought. Reconciliation was essentially impossible in this scenario. The senior judge did speak with the competition organizers afterwards, in the hopes that the stubborn brewer would not be invited back in the future. A more confrontational approach would have the senior judge speak with the organizers as soon as the incident started, but this isn’t always practical. This case is mentioned simply to illustrate the extremes of what can actually happen in judging, and the need to keep a flexible approach in reconciling scores. Hopefully, most judges will be able to talk to the other judges and not run into that situation.

One critical item to remember is that you might be the one who is wrong. Don’t be so overconfident in your skills and rank that you won’t listen to other views. Don’t be like the pro brewer in the previous anecdote: keep an open mind. When your judging partners say they detect something, try to find it—you might have missed it the first time. Ask your judging partners where and how they detected the characteristic you missed (e.g., was the flavor detected in the initial taste, mid-palate, or in the finish?). It’s possible your judging partner is misperceiving something; however, give them enough respect to re-taste. Judging is subjective, and different judges have different sensitivities.

Finally, if a score has been changed significantly as a result of a discussion, make sure the comments on the scoresheet have also been adjusted to match. It is very confusing for an entrant to read a scoresheet where the score and comments seem unrelated. Sometimes it may be best to make note of the reason for changing your score in the Overall Impression section so that the entrant understands that your score may not completely reflect your initial perceptions. It’s much better to have comments be consistent with the score on a scoresheet than to have score sheets from multiple judges have suspiciously identical scores.

Thoughts on Mead Judging

This essay by Kristen England contains observations about mead judging that don’t fit elsewhere. These tidbits cover various situations that can arise while judging and how one judge chooses to handle them. While not hard-and-fast rules, these thoughts should be considered best practices. Similar discussions can be found online in the Advanced Judging FAQ in the BJCP Forum (found on the BJCP website).

Just as wine does not taste like sweet grapes, mead should not simply be a cloyingly sweet honey cocktail. While honey character should be evident, the mead should also be balanced and drinkable. Inasmuch, judges should consider all of the following aspects when evaluating a mead:

On Bias

Most people prefer sweet meads to dry, carbonated to still, and sack strength to hydromel. You must understand your own preference in order to keep it from biasing your judgment. Point short, do not let your mead liking/wanting to influence your mead judging.

On Quantitative Levels

Although the entrant must specify the carbonation level, sweetness and strength, judges often place too much emphasis on these indicators during evaluation and scoring. It would serve a judge well to be aware that a person’s perceptions of sweetness and carbonation levels are extremely subjective. Give the entrant the benefit of the doubt and take everything with a grain of salt. If the entry is completely off the mark, the following point deductions should be made off the top of the total score:

- -3 points = Two levels off (e.g., sweet but entered as dry, sparkling but entered as still)

- -1 point = One level off (e.g., sweet but entered as semi, petillant but entered as dry)

On Drinkability

First and foremost, ensure that the mead is readily drinkable. Lighter, drier meads will be more delicate and quaffable. Sweet meads, which are more like dessert wines, will be much “heavier” and not as refreshing. In either instance, both should be finished products (properly fermented or attenuated, properly aged or conditioned, and readily drinkable).

On Honey Varietals

Each varietal should reflect its monofloral description. It’s very important to note that there is always some variation due to source region, year/season collected, and climactic conditions during the growing season. Just ensure that the mead is following the “theme” of the variety. Sweeter meads will always have more varietal character simply because more honey was used in their making. If possible, a description of the honey variety should be provided. If one isn’t, do your best by looking for common floral markers, and seeing if a noticeable varietal character is present (even if you don’t recognize it).

On Adjuncts

Be sure you understand what adjuncts are present, and what character they provide to mead. When in doubt, ask other judges and keep asking until you find the answer. There are so many things that can be added to a mead that it does the entrant an injustice if you don’t ask a simple question.

- Pyment specific: Grape varieties are not always to be thought of as wine varieties. For example, chardonnay grapes are not inherently buttery even though a lot of chardonnay wine is buttery.

- Levels: The adjunct should never completely overpower the mead. The levels can be very high but one should be able to detect either the honey (varietal) or the fermented honey character.

On Balance

There are three components that need to be addressed when thinking about balance in a mead: sweetness, acidity and tannin. These vary by the type of mead. Sweeter meads will need a greater amount of acid to balance them than drier meads. Traditional meads will have nearly no tannin as honey doesn’t naturally possess it. Grapes, berries and stone fruits usually contain quite a bit of tannin from their skins. Same theme goes for acidic fruits. Importantly, there should be a crispness to the finish of every mead no matter the sweetness to keep it from being flabby. Finally, no mead should have a “raw” or unfermented honey flavor.